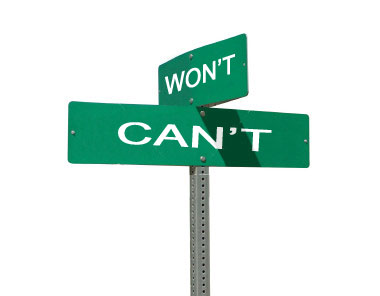

I Can, But I Won’t

by musingsofanaspie, musingsofanaspie.comNovember 16th 2012

In Ten Things Every Child with Autism Wishes You Knew, Ellen Notbohm talks a great deal about the difference between “can’t” and “won’t.” Often for children on the spectrum, behaviors that appear defiant are actually a result of the child’s developmental deficits. It’s not that Johnny doesn’t want to clean up his toys and get ready for bed. He literally has no idea where to begin so he does nothing.

Understanding the difference between can’t and won’t feels huge to me as an adult. So much of what I struggled with as a child was treated by the adults in my life as a simple refusal to try. I was endlessly prodded to do things like have more friends and participate in class. While my parents and teachers seemed to think I just wasn’t trying hard enough–after all I was a smart, likeable little girl–to me it felt like I was making a superhuman effort.

Raising my hand to answer a question in school required overcoming all sorts of fears: the fear of being wrong, of being ignored, of being teased, of not being understood or heard, of being asked a follow-up question that I didn’t understand or couldn’t answer.

I learned early on that there were many things that could go wrong and only one scenario in which everything went right. Those odds weren’t exactly encouraging.

Like so much of what I struggled with as a kid, I’m not sure whether this was a case of can’t or won’t. There were certainly elements of can’t–particularly when it came to being able to express my thoughts clearly and respond spontaneously to follow-up questions. But there was a large measure of won’t born from the can’t.

If you fail enough times, it’s inevitable that trying becomes too costly.

As an adult, I don’t think there is anything I can’t do because of my Asperger’s. I’ve learned enough hacks and workarounds to navigate life on a daily basis.

Won’t is another story.

The older I get, the more resistant I’ve become to activities that are going to have a high emotional cost. There is a long list of things that I don’t want to do–that I won’t do–even if I can.

Notbohm defines can’t as a lack of knowledge, ability and opportunity. Won’t, she says, is about backing away from difficulty and challenge.

Middle age has become the season of won’t for me. I can go to every social event that my husband gets an invite to, but I won’t. I can seek out more opportunities to practice social skills, but I won’t. I can try to make friends, but I won’t.

The gulf between having the ability to do something and wanting to do it has widened as I’ve grown older. I no longer see as much value in toughing something out. I’m no longer as eager to grit my teeth and just get through an event. My desire to fit in lessens with every passing year.

I’m sure there are people who would tell me this is unhealthy and limiting. It may be, in the sense that I’m missing out on potentially enriching experiences. Perhaps at some point I’ll find some of those experiences attractive enough that I’ll want to give them a try. My won’t list isn’t set in stone.

But right now I’m at a point in my life where I’m not interested in enrichment so much as peace. There are days, a lot of days, when I’m content just to be left alone, to not have to deal with the confusing muddle of social interaction that is constantly scratching at the door to my mind.

As I grow older, I find myself becoming more and more okay with my list of won’ts. They no longer feel like the failures they once did.

In fact, it’s no longer a matter of everything coming down to the deficit-based can’t versus the failure-to-try-based won’t, as Notbohm frames the childhood paradigm. As autistic adults, we have the option to step beyond the deficit/failure-to-try model and simply decide that there are things we prefer not to do, just like everyone else.

Original Page: http://pocket.co/sh3LU

Shared from Pocket

Comments

Post a Comment